Audio

Abnormal is the New Normal

Abnormal the New Normal

Ruckhaus©2020

Much of the current framework of rational, equilibrium-based economics is clearly destined, and soon for the dustbin of intellectual history—Mark Buchanan

The Covid 19 pandemic has upended our worlds with ferocity and speed. I am no exception. I can say in honesty, however, that I anticipated 2020 to be a rough year with radical challenges. Along with Peter Turchin several acquaintances of mine who keep attuned to such things spoke of something big coming down in the next few years.

Of course, from my Pentecostal days I am reminded of the powerful belief among many Christians that an “end times” will inevitably come. They scour the biblical texts like forensic investigators on a crime scene seeking secret clues to the impending disaster and their rescue from it. The history of “end times” thinking leads me to believe that once again they will be sorely (and sometimes tragically) disappointed.

Ironically, the survivalist store just down the street from me went out of business, just when it seems they’d be doing a booming business.

As I always have bigger plans for myself than my energies permit, I wanted to start a blog series called “Chronicles from the Collapse” last year. Now, I can’t sound so prophetic. Nonetheless, ever since I started research for my last book, my conviction has steadily increased that our current economic ideology that has so dominated American and world centers for over 50 years cannot be sustained.

A collapse of some kind seems if not inevitable at least readily conceivable from a variety of angles. Karl Marx’s analysis of capitalism not only remains relevant but increasingly likely, prophetic or not. Capitalism—at least the neo-liberal version which many argue is not real capitalism--cannot be sustained because it is fatally flawed. It devours itself. When this gets magnified on a global scale as it is now infused with a pandemic, the potential for societal collapse is easy to envision.

In his book, America: the Farewell Tour, Christopher Hedges envisions a radically altered American nation within just a few years. Hedges refers to an American anthropologist named Joseph Tainter and his work The Collapse of Complex Societies. Tainter’s analysis not only examines some of the major societal collapses in history, but also the explanations modeled to explain it. Tainter’s conclusion finds an economic model to best explain the data. Complex societies collapse and usually remarkably fast when the amount of energy it takes to maintain the complexity of a society has diminishing benefits. In other words, complex societies can collapse when the costs to grow and maintain its problem-solving benefits can no longer be absorbed by its constituents. All shrug with palms turned upward or fingers pointed at someone else when asked who will pay for this or that.

Peter Turchin adds a critical piece to the problem of growth and maintenance in a complex society. It requires more and more elites—small but highly specialized groups who require or demand more of the resources in order to contribute what is necessary. The rest of society cannot support a burgeoning demand among elites. This creates what Turchin calls “the over-production of elites,” and the outcome is one of the main ingredients for societal collapse—competition among elites for less and less resources.

After only a few weeks of shut-down orders coming from the government hoping to stifle an insatiable virus, laments, discussions, and now protests have risen wondering when we can get back to normal. I am among those who believe we will not be able to return to what was—at least not any time soon. Even more so, I hope we don’t. As physicist Mark Buchanan argues in his book Forecast: What Physicists, Meteorologists, and the Natural Sciences Can Teach Us About Economics,[1] the economic mainstream for the last half of the twentieth century has produced “a jaw-dropping discrepancy between economists’ claims and reality.”

The looming economic crisis unfolding is yet but one in a long line of economic “busts” in which economists scramble for explanations as to why few within the discipline foresaw it or knows what to do once it is here. Buchanan relentlessly challenges one of the dominant premises of economics—that markets, if left to operate “free,” will always self-correct. Markets inherently and naturally move toward an equilibrium. We humans just need to basically get out of the way or cooperate.

Buchanan assures that this is a “crazy state of affairs, something more or less equivalent to physics in the Middle Ages.”[2]

This way of thinking, Buchanan asserts, is like “weather forecasters who do not understand storms.” Being an atmospheric physicist, Buchanan relates how economists reason in a similar way to the early meteorologists—the best way to predict the weather tomorrow was to look at how it was yesterday. Unlike economists, however, the emerging field of meteorology stopped being shocked by virulent weather and not only started studying it, but also realized that the best way to understand patterns of “normal” weather was to understand that the earth’s atmosphere is inherently “dynamic” and prone to instability both mild and severe.

To reason as Buchanan then is to say the economics of the last few decades in the near religious belief in the “efficiency of markets” is quite abnormal. That kind of normal we should abandon and not hope to return. Instead, we should understand economics as operating similarly to nearly every other system in the physical world, as normally abnormal. Buchanan calls it an instable equilibrium, a disequilibrium. Markets, like weather, the cosmos and biology are “predictably unpredictable.” To borrow a term from my studies in Old Testament, it is a precarious certainty.

“The biggest shift in scientific thinking of the past fifty years has been the movement to understand these “out of equilibrium” systems, which have rich dynamics, never settle into any lasting state of balance, and kick up perpetual surprises and novelties.” (I wish theology understood this.)

Buchanan asserts that “disequilibrium thinking” puts us on the verge of a “truly revolutionary moment in the history of economics and science.”

Efficiency Without Stability

His main argument centers around the economists’ obsessive focus on efficiency, especially of self-interested rational beings, while ignoring its flipside—stability. The “belief” in market equilibrium is always pushing toward efficiency. It is exclusively technical and mechanical in its orientation, believing that absolute or total efficiency solves all problems.

Buchanan elaborates with patient documentation the absurdity of pushing efficiency with total disregard to the critical other half of the formula—stability. He presents compelling research that loudly accents what conventional economics seems to deliberately ignore—efficient, natural systems in biology and meteorology or in almost every system apart from economics, creates instability. And often the instability can be violent and abrupt.

Jacque Ellul warned more profoundly about the efficiency of technology beginning in the 50s. He held to a maxim that suffocates the notion of unbridled efficiency. Simply put, it is laughable that the “rational” human would be able to control technology. Ellul argues that the very nature of “technique” excludes any notion of intervention. “Technique” is primarily defined as the most efficient way of doing something, and once that gets put in motion, nothing can stop it except non-efficiency, non-technique.

Efficiency marches to its relentless goal all the while creating and energizing the very thing markets fear more than anything else—instability, chaos, uncertainty.

Buchanan would do well to read a little Ellul. He concludes something similar albeit from a very different approach. “We cannot eliminate fragility.” And in fact, he argues from a similar perspective as meteorologists, we can accept that instability is in the nature of things.

Current economics refuses to consider the other half of a good theory. It does not account for stability. Buchanan compares economics to building a nuclear reactor—understanding that nuclear energy is the most efficient—but mixing a variety of fuels without considering the volatility of such a use. It is a case of “build it and hope.” In this regard, the idea that the market is self-regulating is “an act of pure faith.”[3]

Mainstream economics ignores positive feedbacks completely. Like a virus, the more contact between different entities the more opportunity there is for the bad news to spread. Here Buchanan explains how high frequency trading (HFTs) has created a monstrous “network of networks” where one “glitch” sends uncontrollable tremors through the global system. Trading millions of dollars in milliseconds has next to nothing to do with the real economy of exchanging goods and services that most people on the planet engage in, and yet it can destroy it within a few hours. All the while, market thinking keeps pushing that this won’t happen because it didn’t happen yesterday.

A major fault lies in presuming the supremacy of individual ration thinking, all the while ignoring the more critical factor which is the interactions of social groups. The focus needs to be redirected toward understand patterns of group behavior, not individual behavior.

Power of Narrative and Expectations

Buchanan approaches two significant factors that exert more influence over economic movements than individual rational choices that I have explored at length in my doctoral dissertation and in my articles: one is the power of storyline or narrative over individual rational thinking and the second is the power of mimetic desire.

I enjoy it when scientists come around to myth, and Buchanan interjects the power of the storyline or narrative as dominant over “rationality” in human decision-making. “We are hardwired for errant thinking,” Buchanan concludes. The most critical element of human decisions about their well-being are dominated not so much by self-interest as much as how the information required for such choices are “tied together in a coherent story.”[4]

Although probably a casual comment in Buchanan’s book, this idea clarified something that has baffled me.

This confirms much of what I have said and will continue to say. And by the way, it demonstrates how theologists like me can contribute to such discussions. One can hardly study the Old Testament very far without being initiated into a long and bitter struggle with “idols” and their accompanying “storylines.” I present in my last book how the ideological propaganda of imperial divinities dominated the political economy for thousands of years.

Myth building is not about creating interesting stories but infusing a populous with an over-arching narrative of “the way things are.” Those stories primarily deal with the very same thing Buchanan does. They promote an equilibrium that conveniently explains the gross inequities in the distribution of goods. The pantheon of gods and goddesses behave remarkably similar to that of elites. The deities and the elites form in impenetrable cycle of endorsement and authority. The gods sponsor the elites and the elites endorse the gods. The rest serve both.

The second factor is mimetic desire which Buchanan and many current op-ed writers call “expectations.” To clarify, my doctoral dissertation explored the insight of René Girard as to the human propensity to Imitate (mimetic) the desires of others. This mechanism of acquisitive desire made humans both tremendously intelligent and prone to volatility. Kind of like what Buchanan says the markets and earth’s atmosphere are like.

Our expectations, evocations from some clear image of the past, have proven to radically shape our worldview.[5]

“Humans are actually not great or even decent optimizers…Our expectations matter a lot, but they often come not from careful deliberation about what policy makers may do but from what we see others expecting.[6] Imitative desire.

Remedies and Responses

Buchanan lays out what he calls common good solutions to address the economic brain freeze we are in. They all come under the main premise that economics needs to abandon its equilibrium delirium and wholehearted embrace the abnormality of economics. Embrace the inherent instability in economic systems rather than resist it. He suggests creating institutions that research, create models, and provide forecasts of economic movement, like what the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) does for weather. They need to especially focus on the conditions that lead to positive feedbacks.

Buchanan concedes that current economic institutions would have difficulty embracing such a change because they mainly serve private, for profit institutions. Nonetheless, he calls for an economics that serves the common good not the gambling obsessions of the few. He advocates that economic models set up to anticipate dramatic shifts should not be the manipulative occupations of a few, but it should be public knowledge, just like weather reports are. There are lots of jokes about weather reports getting it totally wrong, especially here in Colorado, but honestly, weather modeling does quite well in accurately forecasting general weather patterns. Many lives have been saved because of it.

He also suggests that political policy should act to break up the “network of networks” interdependence that creates the breeding ground for severe economic upheavals.

These are compelling suggestions, but the biggest problem goes beyond Buchanan’s analysis. How can a collective change of mind happen on a massive enough scale to make profound structural changes? All we need is political will it is said, but that is exactly the missing element in a severely polarized world. We are still faced with a bottom-line problem from all ages. The wealthy love wealth. They do not and won’t give it up. They have been extremely adept for thousands of years now at conjuring up ingenious and compelling myths of “the way things are” and must continue to be.

But we also have the problem of the population who simply do not understand the internal machinations of our current economic system. Most of us operate with the assumptions of the real economy. We exchange goods and services in hopes of living a decent, productive and fulfilling life. We are mystified by the “markets,” believing that somehow their behavior determines our livelihood, indeed our existence, like the idiosyncratic gods of old. The top ten percenters operate in a near alternative world. It is a world obsessed by ex nihilo gain. How can I get the most out of nothing? How can I make money in my sleep off those who go sleepless for nothing?

As a theologian, I can speak a degree of insight into the issue of narrative-making and mimetic desire. I don’t know how, but I do know what. I don’t know how to get there, but I do know I need to set out as Abraham, going to a promised land though I don’t know the details or the location.

The Christian narrative in this country has been terribly mauled be the protracted marriage of capitalism and free market religion. This distortion of biblical faith, however, has roots in the “wisdom” logic of ancient elites such as Job’s “friends.” If you prosper you are blessed, and if you are favored by God then you will prosper. If that doesn’t happen, then there is a problem with YOU.

Most importantly, The revolutionary narrative of Jesus has turned into its opposite just as Jesus warned (Mt 7:15-28). At times, I despair that there is little I can do to stop or reverse this. In glimmers of resurrection, I find energy to keep trying. I am not an influential person nor an activist. I can keep writing, and that I will do.

The power of change does not reside in me, but I seek to align myself with the One who does generate change.

Buchanan is one among many who dares to conceive of and pour intellectual energy toward moving beyond the abnormality of what we call “normal,” and so I am grateful for his work. Hopefully, the pandemic can jolt us enough to stop being “too afraid to look under the hood of the market, we’re driving onward in the vain hope that banging and grinding sounds will miraculously go away on their own.[7]

[1] Buchanan, Mark Forecast: What Physics, Meteorology, and the Natural Sciences Can Teach Us About Economics. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013. Since I read a Kindle version, citation is of chapter number.

[2] Chpt 1

[3] Chpt 8

[4] Chpt 10

[5] Chpt 9

[6] Chpt

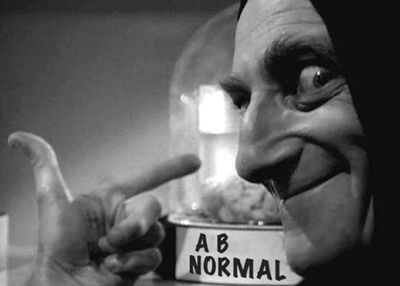

Marty Feldman picking out a new brain for Dr. Frankenstein's new creation in Young Frankenstein